Key Points

- Delhi's location was chosen due to the Aravalli ridge for defense and water distribution.

- British shifted India’s capital to Delhi in 1911, recognizing a seasonal river.

- Modern riverfront development poses flood risks due to intense monsoon seasons.

History always shows that Delhi was built, abandoned, and rebuilt many times, often at nearly the same location.

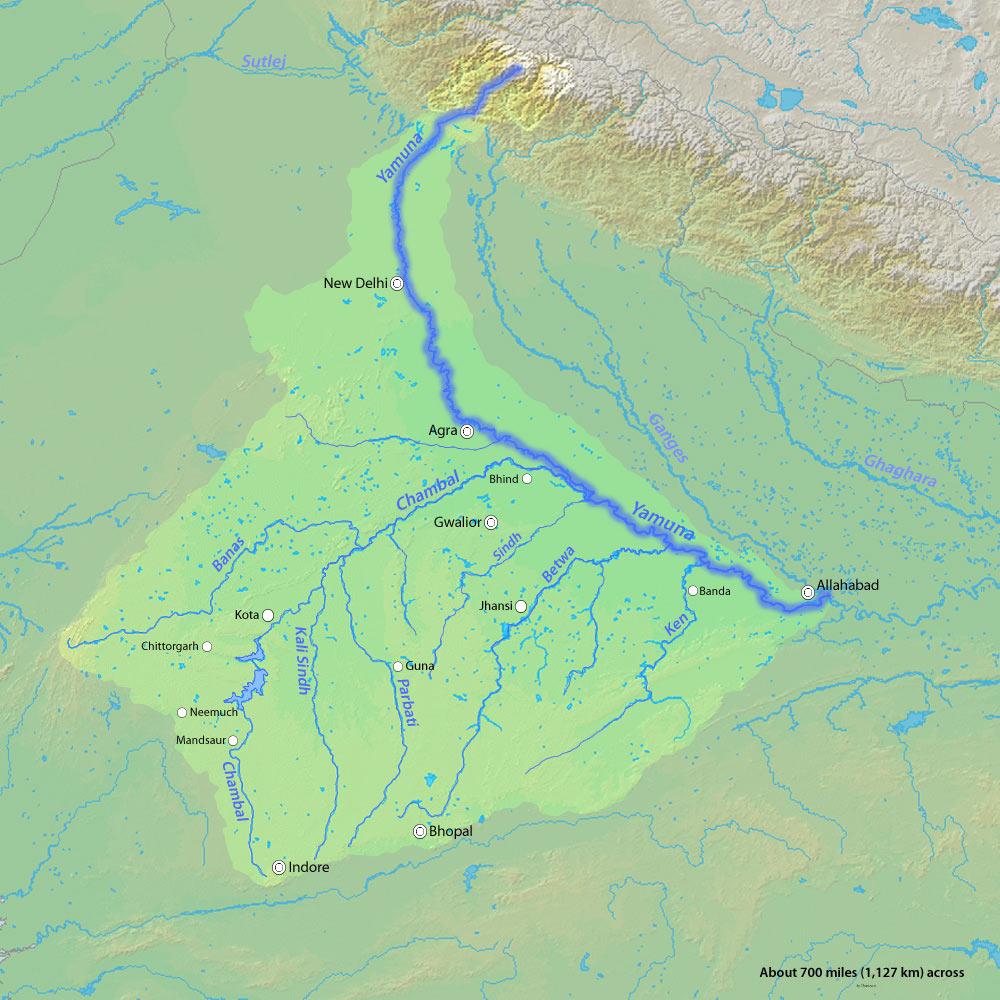

At first glance, this repetition seems puzzling. After all, the Delhi region stretches for miles along the Yamuna—so why didn’t new settlements shift upstream or downstream after earlier cities declined?

The answer lies in geography, ecology, and a level of water wisdom that modern planners are only beginning to rediscover.

Why did Delhi always return to the Same Spot?

The Yamuna alone does not explain Delhi’s repeated settlement. What made this location unique was the Aravalli ridge, running north–south to the west of the river. This ancient hill system provided natural defence and stability that was missing elsewhere along the Yamuna’s course.

Even more important was water distribution. At least 18 seasonal streams once flowed from the Aravallis into the Yamuna, cutting across Delhi from north to south. These tributaries fed hundreds of tanks, lakes, stepwells (baolis), and thousands of wells, forming a decentralised but highly efficient water network.

This system ensured three critical outcomes:

-

No chronic water scarcity

-

Minimal flood damage

-

No recorded famines linked to water failure

In effect, the Yamuna functioned as Delhi’s original town planner.

So, Delhi is situated on the Bank of which river? Now you all the Answer, at the bank of Yamuna River.

Indraprastha and the Wisdom of Ancient Water Planning

Among Delhi’s many historical names, Indraprastha stands out. Indra, the Vedic god of rain and storms, is also known as Purandhar—the destroyer of cities. Yet Delhi survived centuries of intense monsoons.

Why?

Because rainwater was not fought—it was guided. Monsoon runoff was carefully directed into tanks and lakes instead of being allowed to flood neighbourhoods.

After the rains, stored water gradually percolated into the soil, recharging groundwater until the next summer.

This blue infrastructure was complemented by green cover. The Aravalli ridge was forested, and gardens and orchards spread across the city, many of which survive today only as place names and Metro stations.

The Yamuna’s Long Journey: From Glacier to Plain

The Yamuna originates at the Yamunotri Glacier near the Bandarpunch peaks in the lower Himalayas, at an elevation of about 6,387 metres.

| Feature | Details |

| Origin | Yamunotri Glacier (near Bandarpunch peaks, Lower Himalayas) |

| Elevation | Approximately 6,387 metres |

| Total Length | Roughly 1,376 kilometres |

| Terrain | Travels through steep Himalayan valleys before entering the Indo-Gangetic plains |

| Major Tributaries | • Tons (supplies nearly 60% of the water) • Giri • Rishi Ganga • Chambal • Betwa • Ken • Sind |

| Change in Plains | Upon reaching the plains, the river's natural rhythm changes significantly |

Source: Central Water Commission

However, once the river reaches the plains, its natural rhythm changes.

Source: Delhi Development Authority

Barrages, Canals, and a Fragmented River

In the plains, the Yamuna is heavily regulated by barrages at Dak Pathar, Hathnikund (Tajewala), Wazirabad, and Okhla. Water is diverted into canals for irrigation, power generation, and drinking supply.

By the time the river reaches Delhi:

-

Most freshwater has already been extracted

-

In dry months, barely 10 % of the Himalayan flow reaches the city

-

Downstream of Wazirabad, the river is sustained largely by treated and untreated wastewater

As a result, the Yamuna no longer behaves like a continuous river for much of the year. Hydrologically and ecologically, it functions as five distinct segments, each with different characteristics.

Colonial Delhi and the Vanishing Rivers

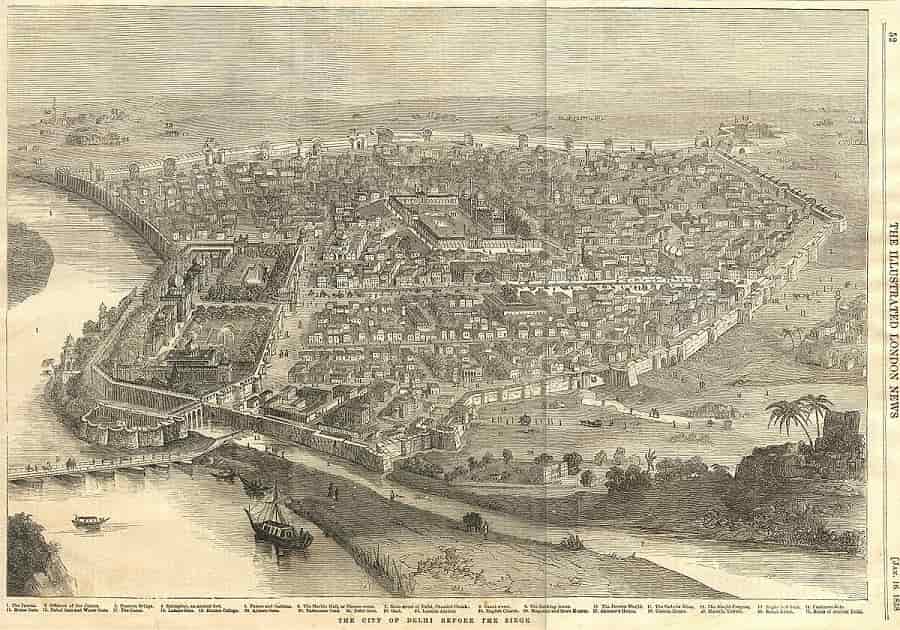

When the British decided to shift India’s capital to Delhi in 1911 at the Coronation Durbar by King George V as the Capital of British India, Edwin Lutyens personally surveyed the landscape—famously from the back of an elephant. Contemporary accounts describe a beautiful seasonal river flowing through what are now Lodhi Gardens and the India International Centre, crossed by a stone bridge.

That river originated near Safdarjung’s Tomb, passed through today’s Khan Market, filled the moat of Purana Qila, and finally merged with the Yamuna.

Source: common wikimedia

Today, it no longer exists on maps.

The question is not where did Delhi’s rivers go?

The real question is: why did we allow ourselves to forget them?

What is the Riverfront Development? Is this in Progress or Risk?

Modern proposals to reshape the Yamuna’s floodplains—often inspired by the Sabarmati riverfront—promise economic growth and urban renewal. But they also raise serious concerns.

Unlike European rivers, Indian rivers operate under one of the world’s most intense monsoon systems, where most annual rainfall arrives within four months. Straightening, embanking, or narrowing a naturally meandering river can increase flood risk rather than reduce it.

If heavy rainfall occurs in the Yamuna’s upper catchment, the river may overflow beyond engineered boundaries, inundating areas far larger than the land reclaimed for development.

Such an event should not be dismissed as a “natural disaster.” It would be a planning failure.

Conclusion

Delhi’s long survival was never accidental. It rested on respect for natural drainage, distributed water storage, and harmony between rivers, ridges, and settlements.

As pressures of urban expansion grow, planners face a choice: work with the river—or repeat the mistakes that once destroyed cities elsewhere.

If history is taken seriously, Delhi need not be abandoned again.

But that future depends on whether the Yamuna is treated as a living system, not just a real-estate boundary.

So, I hope, now you all know, Which River Flows Through Delhi? For more such types of articles, do Visit on Jagran Josh regularly!

Comments

All Comments (0)

Join the conversation